Particle Tracking

Tracking particles in fluid flows is an important step in simulations dealing with multiphase processes. In Computational Fluid Dynamics particle tracking is used for different applications, such as streamlines tracing and the simulation of particle laden flows.

In in-flight ice accretion simulations, particle tracking is used to solve the water droplets field in the particle laden flow of droplets and air around aircrafts. It’s main goal is to compute the so-called collection efficiency, which relates the mass of water collected at a given location on a surface to freestream conditions (i.e. Velocity, liquid water content and time of exposure to wet conditions).

Particle traking is therefore an important block of every ice accretion simulation code.

In my research I have dealt with the implemetation of both Lagrangian and Eulerian particle tracking codes.

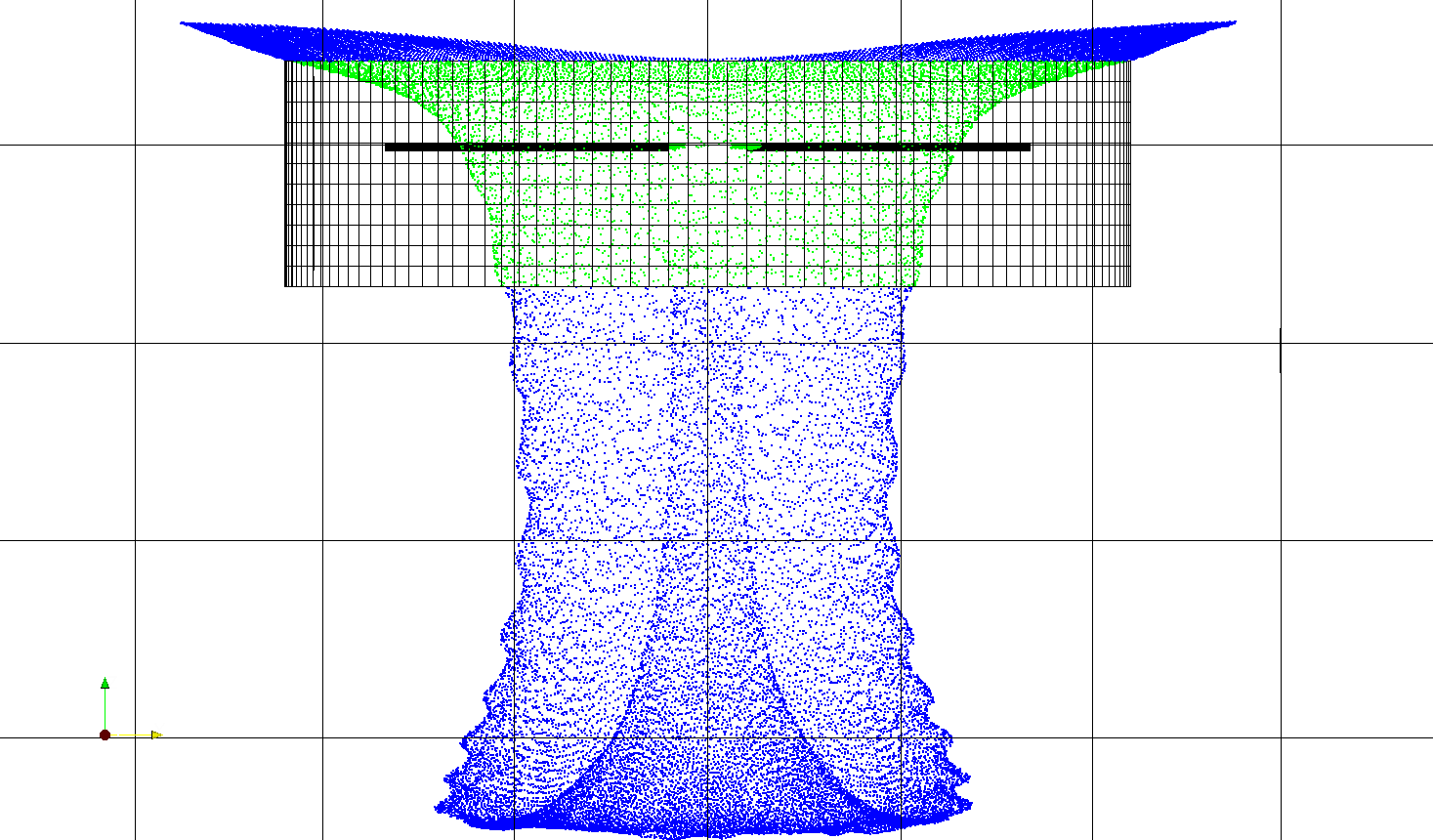

In the Lagrangian frame of reference the trajectories of groups of particles of similar properties called parcels, are computed directly by solving an ODE (Newton’s second law). This allows for a straightforward modeling of physical phenomena such as aerodynamic breakup, droplet deformation, and droplet-wall interaction. This task is embarassingly parallel, in the code this is exploited by using an hybrid MPI-OpenMP parallelization. The picture below shows one of the features of the Lagrangin particle tracking code, which is that of working with sliding and deforming meshes. Here particles are tracked across an helicopter rotor in hover. The rotor is embedded in a cylindrical mesh that is moving inside a larger still mesh.

Particle tracking can also be performed in an Eulerian frame of reference. Particles are treated as a continum, and a nonlinear system of equations is used to decribe the dynamics of particles concentration and velocity. The upside of using an Eulerian description is that the data-structures and methods commonly used for the solution of PDEs can be readily employed. Another benefit of the Eulerian approach is that of not being dependant on the number of particles as the Lagrangian approach. The main drawbacks are instead the inability to describe phenomena as trajectory crossing and polydispersed particles. The latter is dealt with by performing one simulation for each size in the particle size distribution.

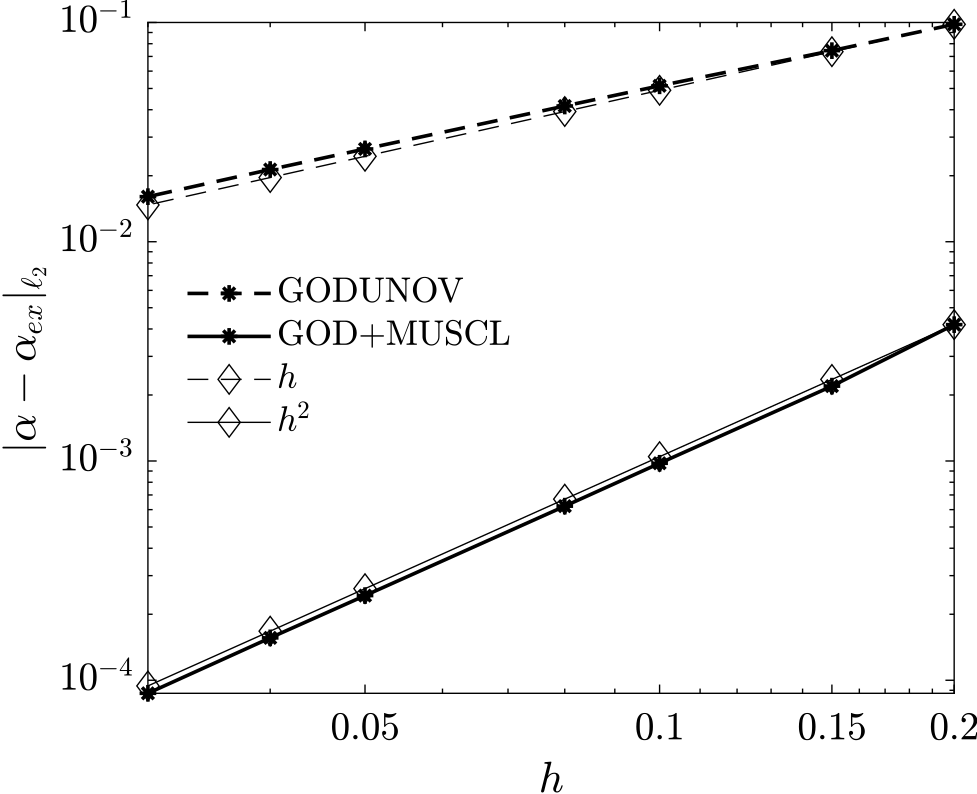

An eulerian one-way coupled particle tracking solver was implemented in the FV solver of SU2. The particle tracking code solves a relaxed form of the equations in order to make the convective part of the system strictly hyperbolic. The convective fluxes are computed by solving the exact riemann problem at each edge (they correspond to the bounaries of the finite volumes in the node centered FV discretization implemented in SU2) by extrapolating the variables at the interface using a limited MUSCLE approach. The source terms (compling the particle pahase to the air flow) are integrated in each control volume using a constant approximation. The equations are marched to steady state using a time marching approach with local time stepping for convergence acceleration. The pseudo-time integratin is performed implicitly using the implicit Euler scheme. The resulting scheme is second order in space as shown in the picture below. The results where obtained by using the Method of Manufactured Solutions (MMS).

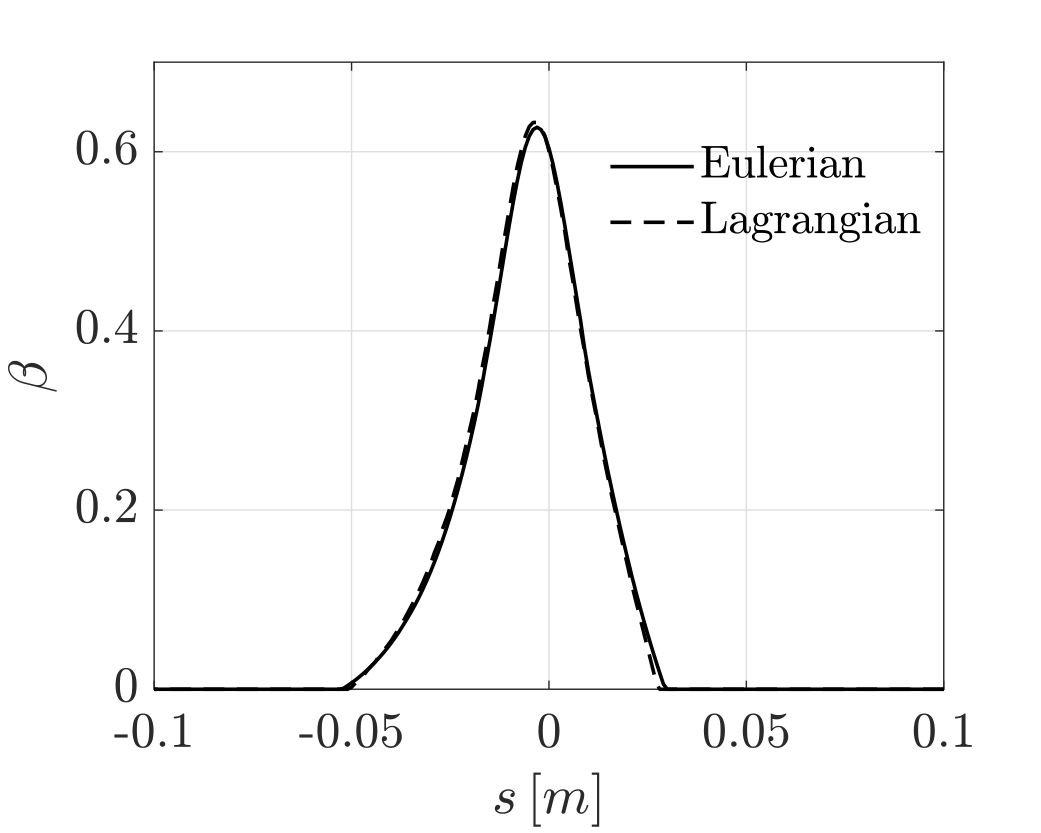

The goal of the particle tracking software is that of computing the amount of water that is intercepted by aircraft’s surfaces flying through a cloud. That is usually done by computing the collection efficiency. In the next figures, both the Lagrangian and Eulerian codes where used to compute the collection efficiency on a NACA23012 airfoil. It can be seen that both methodologies give us the same result, thus proving the correct implementation of the Eulerian solver.

Here we show the particles concentration around the airfoil, computed with the Eulerian solver. THe picture shows the shadow zone aft of the leading edge where particles are not present (their concentration is very small, zero in an ideal world).